Like many of the primary and secondary sources such as books, photos, musical instruments, and historical newspapers held at AOK Library, the source I am choosing to highlight as an introduction to MEMS materials in Special Collections sparks questions about cultural identity and the preservation of history, and has been translated into multiple languages.

Leo Africanus: Mediterranean Patronage and Diplomacy in Africa

Amongst some of the oldest books held in Special Collections was one originally written by a man known by many names and more than one religion; who traversed the Middle Eastern desert, the Mediterranean Sea, and the interior of the often mystified sub-saharan early African kingdoms. Leo Africanus (“Leo the African”) was a sixteenth-century scholar and diplomat from the Islamic state of Al-Andalus, who eventually gained popularity with the educated population of the Mediterranean. Most notably, this is one of the first ever works of popular European literature published about African geography, history, and travel. The version held in UMBC Special Collections is part IX in a series, mostly highlighting North Africa.

Amongst some of the oldest books held in Special Collections was one originally written by a man known by many names and more than one religion; who traversed the Middle Eastern desert, the Mediterranean Sea, and the interior of the often mystified sub-saharan early African kingdoms. Leo Africanus (“Leo the African”) was a sixteenth-century scholar and diplomat from the Islamic state of Al-Andalus, who eventually gained popularity with the educated population of the Mediterranean. Most notably, this is one of the first ever works of popular European literature published about African geography, history, and travel. The version held in UMBC Special Collections is part IX in a series, mostly highlighting North Africa.

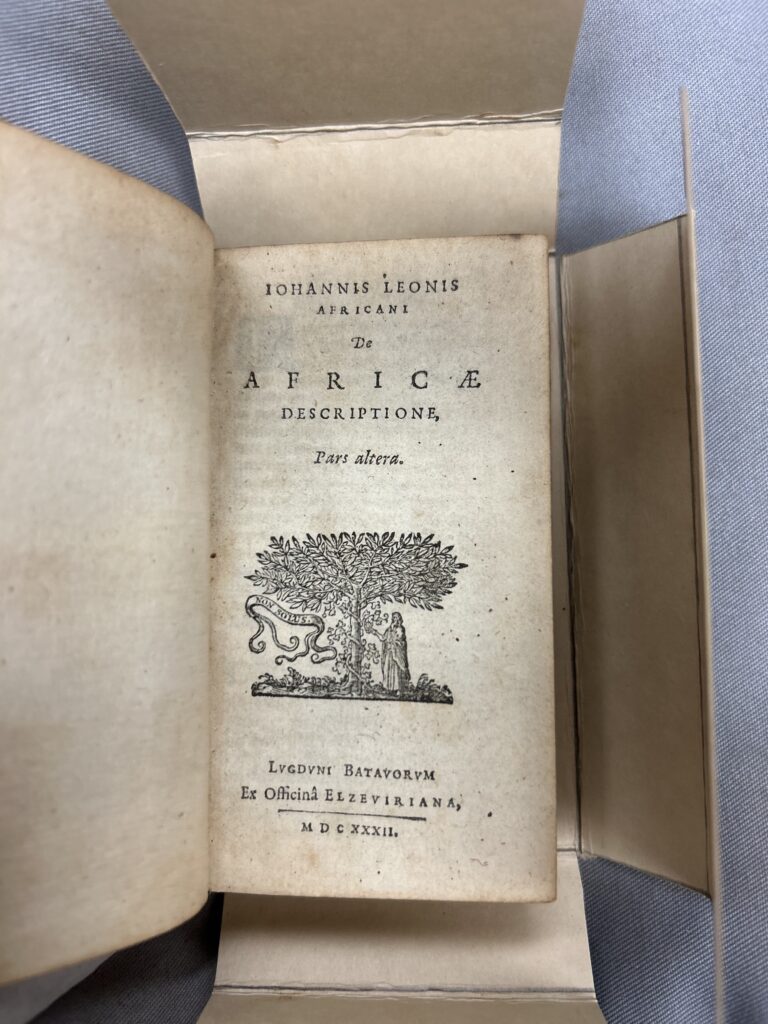

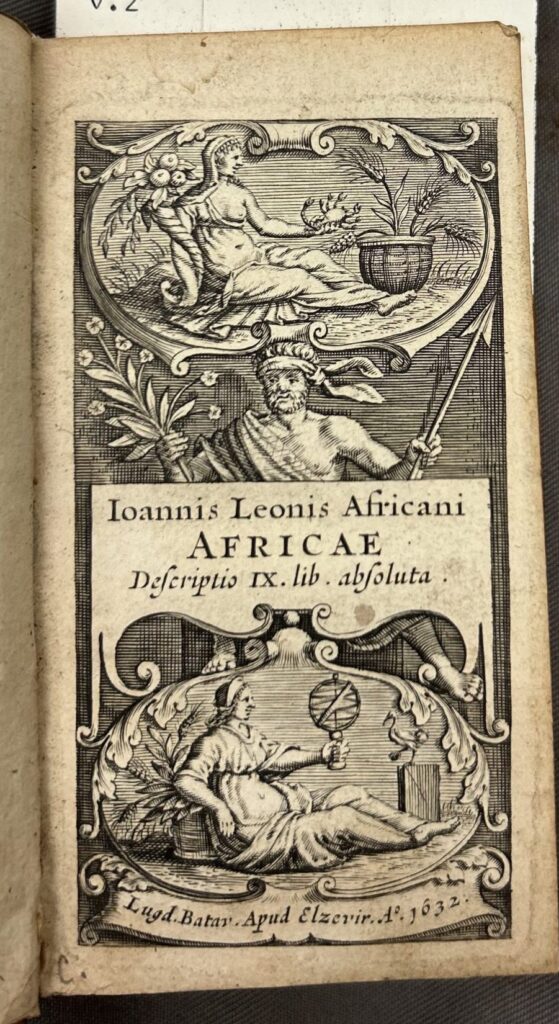

This book in the series is titled Ioannis Leonis Africani Africae descriptio (“Description of John the Lion of Africa”). This version is in Latin and was published in 1632 by a Dutch bookseller. The author, whose birth name was al-Hasan Muhammad al-Wazzan, was also known by the Italian moniker Giovanni Leone (signifying his conversion to Christianity) and “Leo the Moor” (signifying his North African heritage). Leo Africanus first wrote his geographic history of Africa around 1526 and the manuscript was later published by a Venetian geographer, Giovanni Battista Ramusio, in 1550. Interconnected by merchant cities, the late Middle Ages were multi-ethnic and multicultural, with religious diversity and fluidity for individuals and larger communities.

While few Western Europeans had the finances to travel to different continents by sea during the 16th century, many books and pamphlets with topics ranging from satire to politics to theater to geography were produced that referenced North Africa and sub-Saharan African peoples and cultures. The source was the most prominent and one of the earliest written accounts of late medieval Africa. Al-Wazzan wrote this international sensation based on his travels to several African cities and kingdoms in the early 1600s. He exposed Western European literate people and those they socialized with to both the Islamic world and African polities south of the Sahara desert. The English translated title of his nine-part book is The History and Description of Africa and the Notable Things Therein Contained. According to Ramusio himself, al-Wazzan learned to read and write Italian while he was in captivity, translating his text from his original Arabic writings about his travels and about global history.

“Leo the Moor” is sometimes shrouded in mystery when it comes to narratives about his religion and his life, which tells us that his late 15th-century upbringing was dynamic, but also dangerous at times. Folktales and oral traditions, which are written about al-Wazzan and the African traditions he wrote about, have permeated through time and are discussed in the 21st-century by scholars and everyday people. The Mediterranean region, from Istanbul to the Iberian peninsula was influenced by Leo’s presentation of the Sahel region of North West Africa throughout the 17th-century. Al-Wazzan was born in Granada sometime in the mid-1490s, in al-Andalus (then an Islamic Emirate state, now Spain). However, during the Spanish Reconquista, around the turn of the century, he and his family fled to the city of Fez in Morocco. This was the case for many Muslim and Jewish residents of early modern Spain and Portugal, who experienced forced expulsion, covert assimilation, or death due to the imposition of Christianity in a now “united” Spain. In Morocco, a Muslim Berber kingdom in the Sahel region, he found employment with the Sultan of the Wattasid dynasty.

It was in this role that al-Wazzan accompanied his uncle, an ambassador, to the Songhai territory in West Africa as a teenager. There, he began his long career as a diplomat and scholar, traveling to many African states, including the Hausa kingdoms of present-day Nigeria, Jewish communities in Libya, and Timbuktu (present-day Republic of Mali). In addition to observing indigenous African politicians, clerics, civilians, and mercenaries, he encountered other foreign groups like Sicilian privateers and Portuguese settlers in sub-Saharan West Africa by the 1520s. It was on one of these early diplomatic trips in the late 1510s that al-Wazzan was captured on the Island of Djerba (off the coast of Tunisia) by Christian mercenaries who wanted to kidnap him as a “present” for Pope Leo X. Much of al-Wazzan’s nomadic lifestyle is accounted for through his own writing and by the political figures (including Popes and kings) who came to know of his intellectual reputation before they even met him face-to-face.

Tales of “the Moor” being a highly-valued political hostage, known for his knowledge of multiple cultures and geography, had begun to spread across the Mediterranean region by the time his history of Africa was published. Travel literature would become even more popular in 18th-century Europe and self-identified historians, including Leo, wanted to relay clearer and more accessible narrations of past and recent events. The highest ranking official in the Catholic Church, the Pope, was a patron of Leo himself, elevating him socially and in a religious context. Powerful patrons of the arts existed throughout Europe and Italian Renaissance humanists gained a special reputation for wielding both cultural and political power through literature and art. Al-Wazzan’s ability to mold himself into multiple cultures is usually talked about with respect to religion. In 1519, he converted to Christianity (allegedly as a strategy to gain his freedom from imprisonment). Although he would later revert to Islam after his release, his “hybrid-identity” has been long discussed and long questioned.

This was mostly due to the fact that the audience he was presenting his historical literature to were Christian and largely Italian and his readers were aware of his cross-cultural dealings and syncretistic public image. Through writing and eventually printed papers, al-Wazzan demonstrated his knowledge of a plethora of languages spoken in West Africa, including Arabic, Turkish, Berber, Castilian, Hebrew, and Latin. His writings about West and West Central African kingdoms like the Hausa states and fortified cities like Timbuktu and Gao (Mali) prominently mention an unbroken indigenous oral tradition that accounted for leaders and military generals in those regions. For instance, al-Wazzan wrote about how the famous horsemen of the Songhai cavalry impressed the region with military battles. He also wrote about the regions of specific rulers like Muhammad Toure (also called Askia Muhammad I) the first of the long line of Askia dynatry rulers of Gao.

He also described activities of African communities further east, such as Nubian kingdoms along the Nile River in what is now Egypt and Sudan. To the south of the West African Songhai kingdoms there were also groups like the Mossi to the south (now Burkina Faso). Al-Wazzan told a history of many of these societies that dated back to early Antiquity (800 B.C.E to 500 C.E). The same patchwork history he gathered of these many African peoples would eventually be published in 19th-century Victorian London, and though Leo died after he returned to Tunisia around 1554, his work and its relevance has lasted for half a millennium for a Christian, Muslim, and global literary audience.

Newer editions of this book have been published, with one of the first English editions dating back to 1600. Many of the aforementioned versions of “the Moor’s” work include appendices and indexes. This 1632 version of Leo’s original Arabic manuscript was produced in Latin nearly eighty years after the traveler and historian’s magnum opus came to fruition. This geography of contemporary African politics expanded the reach of world history and geopolitics to those who were literate within Latin Christian populations, from a female patron of the arts in a Venetian salon to an English settler in the seventeenth-century Caribbean. The cross-cultural connections in the Mediterranean region between sub-Saharan Africa and mainland Europe are discussed in the text. This small and detailed manuscript would have been an important investment for early modern European humanists.

The courses offered for the Fall 2025 semester at UMBC are not the only way to engage with medieval and early modern history and culture, but I would highly recommend Dr. Susan McDonough’s class on the Medieval Mediterranean (HIST 362) or Dr. Gloria Chuku’s course West African History (HIST 354/AFST 312) for the most relevant syllabi on topics related to Mediterranean and North West African narratives in history. Additionally, the USM library database is vast and searchable and you would be surprised at how many niche topics relating to medieval life you’ll find in a Maryland school mainly known for STEM-related programs. Latin and Wolof (a Senegalese/West African language course offered at UMBC) also can enrich your understanding of ancient, medieval, and early modern cultures around the world and how we can preserve history, art, language, and culture collectively.

Language: Latin

Subject(s): Africa, Description and Travel, Islamic literature, Humanism, Latin literature, Early modern politics, West Africa, Abrahamic religions, Mediterranean history

Call number in UMBC Special Collections: DT7 .L57 1632

Citation: Leo. Ioannis Leonis Africani Africae descriptio IX. lib. absoluta. [Pars prima]. Lugd. Batav: Apud Elzevir., 1632. https://usmai-umbc.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01USMAI_UMBC/41dptd/alma990003062540108247

Related Material:

Late Nineteenth-Century English Translation of the text: Leo Africanus, Pory, John (tr.), and Brown, Robert (ed.). The History and Description of Africa and of the Notable Things Therein Contained, Vol. 3, 1896. https://jstor.org/stable/al.ch.document.nuhmafricanus3.

French edition of Maalouf Amin’s meta-fictional version of Leo Africanus (available at AOK library): Maalouf, Amin. Léon, l’Africain. Paris: J.C. Lattès, 1986. https://usmai-umbc.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01USMAI_UMBC/1dfu4bv/alma990016802480108247

Abulafia, David. “MEDITERRANEAN HISTORY AS GLOBAL HISTORY.” History and Theory 50, no. 2 (2011): 220–28. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41300080.

Black, Crofton. “Leo Africanus’s ‘Descrittione Dell’Africa’ and Its Sixteenth-Century Translations.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 65 (2002): 262–72. https://doi.org/10.2307/4135111.

Davis, Natalie Zemon, and publisher Victoria University . Centre for Renaissance and Reformation Studies. Leo Africanus Discovers Comedy : Theatre and Poetry across the Mediterranean. Toronto: Centre for Renaissance and Reformation Studies, 2021. https://usmai-umbc.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01USMAI_UMBC/1dfu4bv/alma990062351160108247

Big Ideas (S06 E40 – Natalie Zemon Davis on her book Trickster Travels https://www.tvo.org/video/natalie-zemon-davis-on-her-book-trickster-travels

Ewa, Ibiang Oden. “PRE-COLONIAL WEST AFRICA: THE FALL OF SONGHAI EMPIRE REVISITED.” Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria 26 (2017): 1–24. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48562076.

Fisher, Humphrey J. “Leo Africanus and the Songhay Conquest of Hausaland.” The International Journal of African Historical Studies 11, no. 1 (1978): 86–112. https://doi.org/10.2307/217055.

Green, Monica, and Brian Long. Constantinus africanus. Blog. December 22, 2017. https://constantinusafricanus.com/2017/12/22/ego-constantinus-africanus-montis-cassinensis-monacus/.

Kaufmann, Miranda. Black Tudors: The Untold Story. Paperback edition. Oneworld Publications, 2018.

Khalifa, Mahmoud Abdelhamid Mahmoud Ahmed. “Amphibious Storytellers in Leo Africanus and The Moor’s Account : Exiles and Nomads as Bicultural Humanists.” Arab Studies Quarterly 45, no. 3 (July 15, 2023): 212–28. doi:10.13169/arabstudquar.45.3.0212. https://proxy-bc.researchport.umd.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=hia&AN=164879906&site=ehost-live&scope=site

Starczewska, Katarzyna K. “Leo Africanus’ Contribution to a Latin Translation of the Qur’ān: A Case Study of Intellectual Activity after Conversion.” Studi e Materiali Di Storia Delle Religioni 84, no. 2 (December 2018): 479–97. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=hia&AN=135675793&site=ehost-live&scope=site